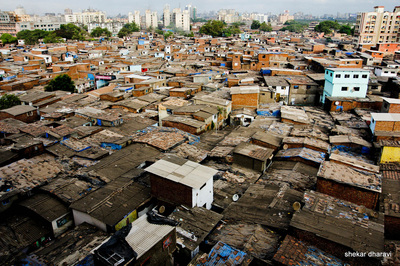

What makes Dharavi so unusual isn't it's size, oppressive living conditions or human density, as unknown to many people, there are actually other slum areas in Mumbai close in size, but it is the fact that it is also a mature and complex economic zone with miniature (some as small as bedroom-sized) factories and recycling plants that produce close to $500 million dollars in GDP for India.

It is estimated that out of the 20.5 million people living in Mumbai proper, over 6.5 million live in squalor conditions, so there are many slum neighborhoods like Dharavi, and even one right outside our apartment complex gate for instance (image our surprise arriving on the redeye and driving past tin shacks and tarp houses almost all the way from the airport to our front gate in the dark. We were worried for a moment.)

Oh and a disclaimer: all of the pictures above and below are actually from Dharavi, but they are not mine and are from professionals posted on Google Images. It is advised not to take a camera in, less for safety and more out of respect.

I did not take the kids with as they would have not been able to handle the sights or the lack of safe walking conditions in certain places, nor did Suzanne go with as she would have really been out of place. In the factories and shops it was exclusively men, and the women I encountered were mostly in the tiny one-room homes (more in a bit).

Oddly, while walking very few people looked my way, far less than a regular Mumbai street - either they are used to seeing tourists, or just by myself with a local tour guide I was less a spectacle than usual as a family of five, tall pastey Europeans. I did run into one other tourist, however, and he was from the Bay Area (go figure, us curious Liberals).

The three main areas of Dharavi are market streets, micro-production factories, and housing. The market streets are nothing out-of-the-ordinary for Mumbai, save for perhaps an additional chicken or goat, or Brahman Bull pulling a cart (with full Hindu paints, decorations and garnishes). The Micro-factories are incredible with paper and plastic recycling being one of the most prominent activities. The city garbage services sort through trash and bring all of the recycling goods here, where residents stand waist-deep in mountains of paper and plastic hand-sorting by color, weight and material type. They are next cut down, shredded and processed. Other key recycling businesses are aluminum smelting, paint-can cleaning and cardboard re-cutting. All of these tasks are done in small rooms in incredible heat and dangerous conditions by half-dressed men with no safety equipment, let along full-clothing or shoes.

Production and processing of new goods such as leather, fabric dying, sewing and pottery are also key, and in their own separate quarters. As currently occurs in China, South America and even America in the last century, many of the workers are migrants from the rural areas who will work for any pace in any conditions for a few Rupees a day and a dirty mattress above the factory. For the most part, it is normal that they work 12-hours per day, 6-days a week.

The third-part of the tour, and the most disorienting portion, is the housing. The top 20% who run many of the companies live in run-down government high-rise housing typical of many U.S. cities (but the building are heavily soot stained and with laundry drying in every window in the dirty breeze). The remaining 80% live in one-room hovels that do have electricity, but with no running water or sewers. If you're lucky, your one room with ten family members is on an outside lane, but if not...

Here is where I have to pause and say I wished I was a much better writer, because when we turned down a dank, ever-narrowing lane to see the inner slum-rooms, it was beyond my range of words. If you could imagine in your mind an expensive movie-set made to look like the tightest, most gruesome, grim dsytopia possible, you'd be getting close to what I saw. I felt like I was in an underground warren of tragically displaced and suffering people after an Apocalypse.

The inner passage-ways were about 3-feet wide by 5-feet tall and mostly pitch black (and this on a bright and sunny day). There were lights on in the some rooms and the doors were just blankets. Above was a tangle of random metal supports and jagged tin edges, plus loose electrical wires. Beneath was flowing, raw sewerage. It was like being a rat in a dark maze, or being in a bad dream.

And for many, many people, this is home.

When we emerged back into the sunlight, I immediately thought, how will I ever explain what I just saw to anyone? It was one of the most unusual sensations I have ever experienced. And definitely 'first-person slum voyeurism'.

My Guide was a wonderful guy and as we parted he helped me hail a cab and even did the inevitable arguing for me - for you see in India, if you do not have a pre-paid car service and driver, every common-cab boarding-procedure is an long drawn-out argument about destination, fee or something. It just seems like sport to them.

Mumbai is a rich and vibrant city with a huge financial district, Bollywood, many upscale malls and nicely gated apartment buildings. But as a business-friend of mine told me after a trip here 10-years ago, "Bombay (Mumbai) is a funny place, on one side of the street is a modern, state-of-the-art office complex, and directly across the street, a slum with open sewage." Well, it's an exaggeration, but not by much, and we've seen both while here so far, and in a side-by-side mixture that doesn't make sense to our way of life in the U.S. - but there is no avoiding the poor and the slums here in India. And today, instead of just driving by, I had to actually go inside and see that life for myself.

And inside, despite what I experienced for housing, I have to say that most of the people looked productive and happy; busy and with purpose. When I finally asked my guide at the end of the tour if people who became successful typically moved out, he said no, most do not as this is their home. So I offer my honor to those who are happy, and my compassion for those who suffer there. And thank them for letting me respectfully visit their homes and places of work.

But who am I really to presume we know anything about their lives or feelings. They could be happy, or sad, or it might be the only thing they know (except what they see on TV) and perfectly normal. After all I believe they do not need our pity, but our love and compassion. And as the wise Buddha once said...“Have compassion for all beings, rich and poor alike; each has their suffering."

Off my soap box for now...and off to Delhi to see what this whole "best Indian city rivalry" is all about!

- Mike

RSS Feed

RSS Feed